From Islay comes the story of a malevolent fairy, told to Miss Elspeth Stirling by the Postmaster at Portnahaven. A brother and sister were going along a road by a loch when a little man came running past them and touched the boy as he passed. The boy was paralysed for the rest of his life. His little sister, who was wearing green, was uninjured. Paralysis has often been regarded as a fairy evil, but it is strange to find green considered a safeguard. It is generally thought to be a dangerous colour. ….

Again from the Highlands there is an account of a rather unusual nature fairy, the Ghillie Dhu. He haunted the birch woods, dressed in leaves and moss. Osgood Mackenzie in A Hundred Years in the Highlands tells how a little girl called Jessie Macrae was lost in the woods. The Ghillie Dhu looked after her all night and took her home in the morning. After this five lairds, with great ingratitude and hard-heartedness, went out to shoot him; but fortunately they never saw him.

Extracts from ‘Some Late Accounts of the Fairies’, K. M. Briggs, Folklore , Sep., 1961, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 509-519

Papillon Perfumery is a small British independent, established 2014. To date they have released six scents, which have received critical acclaim. Papillon offer a sample pack of 2 mls of all six for £30 plus postage. 50ml bottles are around £130-140.

The perfumer is Liz Moores. She demonstrates deep consideration and careful thought in each scent; they are strong, complex, powerful and lingering. These are the first perfumes through which I felt had entered a distinctive sensory landscape, beyond simply assessing ‘Like/Don’t Like’.

Dryad is my favourite of the set. It is a dry, bitter, earthen, green scent. To me it feels introspective and quiet; old, yet natural and alive. There is a freshness to it, but it is the earthy dark freshness of damp leaves on a forest floor, and of padded cushions of moss and lichen on tree trunks. This is not the freshness of breezes and open green spaces in bright sunlight.

The first impression is quite bitter, with a sense of tannins and bark. It brought to mind gunpowder tea, and a faint childhood memory of a bitter but sweetish medicinal remedy. I realised I was remembering my mum’s ancient battered enamel bowl, stained with dark brown rings, which she reserved for a potion of Friar’s Balsam with boiling water, for us to steam our heads under a towel when we had colds. The notes listed for Dryad are narcissus, oakmoss. jonquil, cédrat, galbanum, benzoin and vetiver. On research, Friar’s Balsam contains benzoin as the decongestant and antiseptic, so this must be my memory trigger.

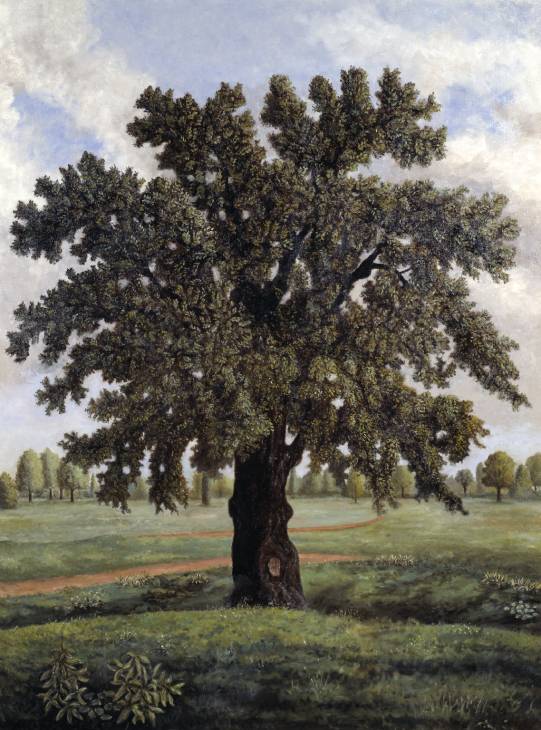

Dryads are tree nymphs or spirits from Greek mythology, usually beautiful young women attached to oak trees (drys = oak). They were shy, except around the goddess Artemis. A dryad protects her one assigned tree; when the tree dies, the dryad dies.

Oakmoss (Evernia Prunastri – image right) is a powerful but lamented ingredient in perfumery. It is a lichen which grows on oak trees around Europe, with a pretty deer’s antlers appearance. The moss is harvested and processed into an absolute in Grasse, France, and is critical to many iconic green and chypre perfumes, such as Guerlain’s Mitsouko. However, in absolute form it can act as an irritant and so has been restricted by EU health and safety legislation. I believe a perfume can only contain a maximum of 1% of oakmoss. This means since the 1990s many classics have had to be reformulated without oakmoss, or synthetic substitutes found. From the listing information, Dryad does seem to use real oakmoss, bringing up such strong impressions of oak trees, bark and bitter leaves.

There is also warmth, softness and sunlight in the scent. As it progresses, it softens more and more, and the bitterness fades away, leaving a sweetness like new hay and cut grass.

The scent makes me think of the quiet power and intelligence of trees, which we do not yet fully understand. I am reading a fascinating book, The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben. He draws on his experience working as a forester in a forest in Bavaria and observing his trees over many years, but also from the latest scientific research. There is a growing body of evidence that trees communicate with each other: through scent messages on the breeze, and through electrical impulses sent through their root structures and highly complex symbiotic fungal systems, dubbed the ‘wood wide web’. They exchange water, carbon, sugars, nutrients, and information about pests and living conditions. Trees can pump water and nutients to a nearby tree when it is in trouble, keeping it alive – even cut off stumps have been seen to be kept alive in this way. Trees are observed to care for their children and relatives, but also to develop mutually beneficial exchanges with neighbouring trees of different species.

When I smell Dryad, I think of a silent green clearing somewhere in an ancient forest of England. I think of green men and sheela-na-gigs carvings, pre-Christian images found in churches across Britain and Europe – ancient things we have forgotten about – and the symbolism of English oaks.

An English Oak Tree – Stephen McKenna – 1981

Green Man carving in Sutton Benger

Below, Sylvia Plath reads her poem On The Difficulty of Conjuring up a Dryad , capturing the infuriating frustration of writer’s block amid the mundanities of daily life, and the difficulty of creating a convincing likeness of nature in art. I had never heard her speaking voice before researching this post, though I read her poems as a teenager. It was almost a shock; her slow, deep, upper-class New-Old England vowels are captivating.

The poem feels like a fitting tribute to Liz Moores and the development of her beautiful Dryad. The more I learn about perfumery, the more I can see it is an art form, as challenging as any other. A perfume can take two years or more to create. A perfumer works within constantly shifting limitations (budget, client briefs, market tastes, deadlines, availability of materials) whilst trying to capture something beautiful and transient – which must also be consistently and repeatedly reproduced.

Text of poem below.

On the Difficulty of Conjuring up a Dryad

Sylvia Plath, 1957

Ravening through the persistent bric-à-brac

Of blunt pencils, rose-sprigged coffee cup,

Postage stamps, stacked books’ clamor and yawp,

Neighborhood cockcrow—all nature’s prodigal backtalk,

The vaunting mind

Snubs impromptu spiels of wind

And wrestles to impose

Its own order on what is.

‘With my fantasy alone,’ brags the importunate head,

Arrogant among rook-tongued spaces,

Sheep greens, finned falls, ‘I shall compose a crisis

To stun sky black out, drive gibbering mad

Trout, cock, ram,

That bulk so calm

On my jealous stare,

Self-sufficient as they are.’

But no hocus-pocus of green angels

Damasks with dazzle the threadbare eye;

‘My trouble, doctor, is: I see a tree,

And that damn scrupulous tree won’t practice wiles

To beguile sight:

E.g., by cant of light

Concoct a Daphne;

My tree stays tree.

‘However I wrench obstinate bark and trunk

To my sweet will, no luminous shape

Steps out radiant in limb, eye, lip,

To hoodwink the honest earth which pointblank

Spurns such fiction

As nymphs; cold vision

Will have no counterfeit

Palmed off on it.

‘No doubt now in dream-propertied fall some moon-eyed,

Star-lucky sleight-of-hand man watches

My jilting lady squander coin, gold leaf stock ditches,

And the opulent air go studded with seed,

While this beggared brain

Hatches no fortune,

But from leaf, from grass,

Thieves what it has.’